We now live in a world where plastics are becoming a part of our marine ecosystems. As a result, we strive hard to clean the plastics from our oceans. Dr. Max Liboiron (Michif-settler, they/she) goes a step ahead and asks: “whose water am I using to clean these plastics, anyhow?”

By shifting the conversation from blame to accountability, Liboiron doesn’t shy away from asking the difficult questions. They argue that colonialism is not a thing of the past but has continued into the present in the form of pollution. Pollution that is happening around us, inside us and by us, every single day. This stance lies in the assertion that pollution is not to be oversimplified as merely an act of environmental damage, but instead to look at it as a systemic act of violence towards a land. Emphasizing on awareness, responsibility and the relationships we share with each other and our lands, they are making unconventional strides in redefining the methodologies that enable current “colonial” practices.

As an Associate Professor in Geography at Memorial University of Newfoundland, they are a leading force in the development and implementation of anticolonial research in a wide array of spaces. They are also the founder of Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR), an interdisciplinary plastic pollution laboratory whose methods emphasise on humility and good land relations. Liboiron developed the interdisciplinary field of discard studies and runs a blog that serves as a platform for the understanding and implementing the same. A staunch advocate for justice-oriented scientific methods, they are an expert in the fields of feminist science studies, discard studies and Indigenous science and technology studies. Their latest book Pollution Is Colonialism will be released by Duke University Press in May 2021.

We took this upcoming pulication as an opportunity and got in touch.

Your upcoming book, Pollution Is Colonialism, bridges the gap between Science and Technology Studies, Indigenous Studies, and Discard Studies. What inspired you to write this book and build these parallels? Who is this book for?

The book began as a text about plastic pollution and all of the ways this form of pollution challenges current wisdom about how pollution works and the role of science and activism in making change. As it developed, these key questions turned the book into a methods text. The main argument of Pollution is Colonialism is that all forms of research and activism have land relations, and those can align with or against colonialism as a particular form of extractive, entitled land relation. It's written for a few audiences: Indigenous readers who know the arguments well and might be looking for nuance and strategy; non-Indigenous researchers and activists who are starting to realize that colonialism, like capitalism and racism, is a dominant organizing force that they have to contend with; and really anyone who wants to think about often invisible power relationships in their work on pollution and beyond.

The main argument of Pollution is Colonialism is that all forms of research and activism have land relations

This kind of work reaches across a lot of disciplines. Science and Technology Studies, Indigenous Studies, and Discard Studies make sense together because they all understand the world in terms of power relations, including how some things come to seem normal, even natural, while other things are discarded, erased, dispossessed, or become unimaginable. But the book also stretches across natural science and social sciences. Because it draws from such a diverse set of conversations, I did a lot of work to avoid jargon and tell good jokes, explain my terms since the same word means different things in different disciplines, and talk across rather than down to different audiences, even when those audiences might disagree on points.

What is anticolonial science and how is it different from a postcolonial approach to science? How can one employ an anticolonial science and what could it mean for the environment at large?

In my imperfect understanding of the different conversations that fly under the banner of postcolonialism, the term refers to a particular set of colonial relationships where the occupying forces have "technically" left but colonial forms of knowing, governance, value, and development are still dominant, like a horrible haunting that you can never shake off. I understand its roots in places like India and parts of northern and western Africa. Because of the -post, a lot of the discussions around postcolonial science is about the never-ending dominance of non-local ways of thinking in science as well as a fair bit of attention to the historical ways that dominance happened.

Anticolonial science, at least how I use and understand the term, is set in North America and the context of settler colonialism and ongoing genocide of Indigenous peoples. It's dedicated to land and genocide as the two core techniques of colonialism--and so how dominant science is part of dispossession of land and genocide, often in ways that seem mundane, uneventful, and normal. The main example in the book is how the permission to pollute system, where regulations allow a certain amount of contaminant to exist in bodies, water, or other environments, is a way to access land for settler and colonial desires and futures, all made possible by removing Indigenous people from that land to begin with (or not, in obvious cases of pipeline and mining protests).

The opposite of colonialism isn't environmentalism

In science, anticolonialism means working in a way that does not assume settler and colonial access to Indigenous land for settler and colonial goals, even when those goals are benevolent, well-intentioned, or environmental, like conducting beach clean ups without Indigenous consent or permission. The opposite of colonialism isn't environmentalism. In fact, environmentalism does not usually address colonialism and often reproduces it. Kyle Whyte (Potawatomi), Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes), and many others have pointed out that environmental solutions to pollution such as hydroelectric dams, consumer responsibility, and appeals to the commons assume access to Indigenous Land and its ability to produce value for settler and colonial desires and futures. As Jodi Byrd has written, environmentalism often "maintains the dispossession of Indigenous peoples for the common good of the world."

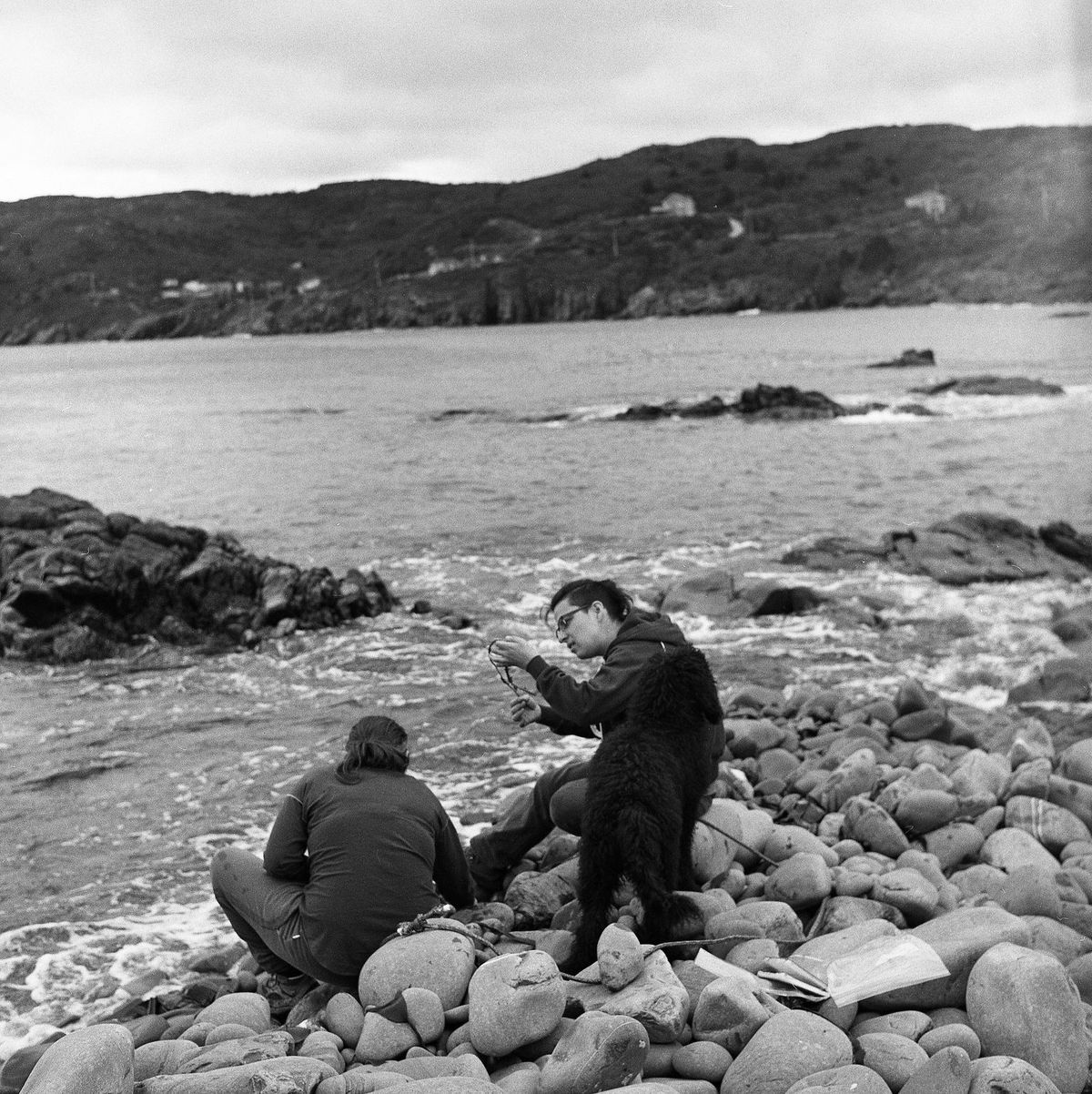

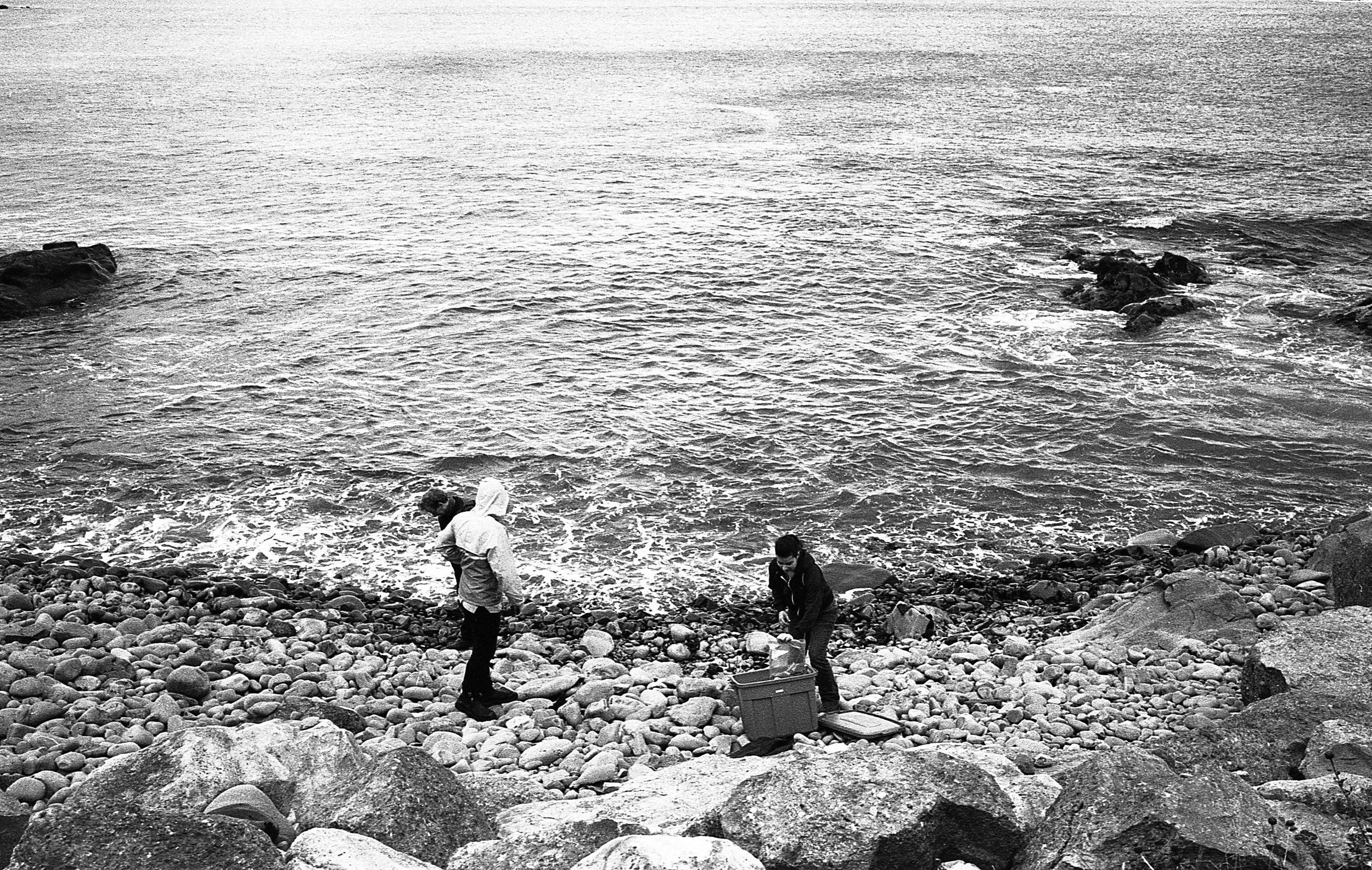

The last part of the book walks readers through some of the anticolonial science techniques we use or develop in my plastic pollution lab, such as being invited to do research by Indigenous groups rather than assuming access, using community peer review, and using judgmental sampling rather than random sampling among others.

An important aspect within your practice is feminist science studies. How does feminist science studies inform your work?

As a graduate student, I was trained in critiques of dominant science, mostly from a feminist science studies perspective. It's a discipline that has a long history of investigating the power relations in dominant science, showing that many claims to objectivity are ways to naturalize control over nature, make Western ways of thinking and values seem universal, and generally being macho, elitist, and imperial. When I came to Newfoundland and Labrador for my current job as a professor, I was ready to critique the plastic pollution science here. But there was none. A conservative government had shuttered and silenced, or never begun, many of the environmental programmes that might have curtailed extractive industries. So I had to do some science! I decided to do science in a way that directly addressed decades of feminist science studies critiques, which meant doing science very differently that I was taught in my early biology classes.

I began to think about how to put equity, humility, and accountability at the centre of all my work

But it's really hard to start a research programme by thinking about what not to do, since you have to do something. There were some key texts, like Mary O'Brien's "Being a Scientist Means Taking Sides" that showed me that choosing a couple of explicit values to base decisions on would be one way to go. I began to think about how to put equity, humility, and accountability at the centre of all my work, from doing statistics to taking out the trash. That's flourished into what we now call an anticolonial science.

Through your work at Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research you aim to illuminate how pollution is not a symptom of capitalism but a violent enactment of colonial land relations that claim access to Indigenous land. How does this view add itself to a growing technological and urbanizing world as today?

I start a lot of my talks and writings with Lloyd Stouffer, editor of Modern Packaging magazine in 1956, declaring that “The future of plastics is in the trash can.” It was a moment when multiple industries--petrochemical, packaging, and consumer goods manufacturers--were dealing with saturating markets. Disposability was a strategy to move plastics and other goods through households, rather than just into them where they would stay and endure.

Disposability assumes access to land. It assumes that household waste will be picked up and taken to landfills or recycling plants that allow plastic disposables to go "away." Without this infrastructure and access to land, Indigenous land, there is no disposability.

Disposability assumes access to land. Without this infrastructure and access to land, Indigenous land, there is no disposability

But technological change and urbanization are not synonymous with plasticization and disposability. Before 1945, plastics were not mass-produced items. They were specialty, often artisan, goods that were meant to replace tortoise shell, shellac, ivory, and other materials extracted from increasingly endangered animals. Plastics made durable goods that were never meant to be tossed away. In short, plastic was environmental. Just because the largest share of plastics worldwide are made into disposable packaging does not mean that is what plastics have to be. Technological change can also mean degrowth, specialization, and creating dynamic and durable items.

One goal of the book is to talk about plastics and science as having other pasts--and therefore other potential futures--than the ones that seem inevitable now. It's designed to denaturalize some of the ways we think about plastics, pollution, and environmental activism.

The approach you take seems very systematic. For instance, rather than asking how much people recycle and why they don’t recycle more, discard studies asks why recycling is considered good in the first place. What are the outcomes of such a line of thinking? What sort of solutions does such systemic thinking bring?

One of the characteristics of dominant systems is that they make some things seem normal and natural to the point that they're taken for granted, like the idea that recycling is good for the environment. But as we now know, recycling is not primarily an environmental good--it produces pollution, allows disposables to continue to be produced, does not conserve or preserve resources. And very little recycling happens at any rate (for more see Samantha MacBride’s Recycling Reconsidered, which I think is one of the best books out there on recycling from a systematic position).

If you don't do what you call systematic thinking, you only ever play in the sandbox the dominant system as already laid out. You can tweak the system, but you can't change it. The example in the book is regulated pollution levels. It would seem like a good thing to regulate industry so it doesn't pollute more that is allowed, more than causes irreparable harm to the environment. This is based on the idea that land and bodies can absorb, metabolize, dilute, or purify some amount of pollution. But this needs land. It assumes settler entitlement to Indigenous land (and often people's bodies in the case of body burdens) for industry production. Even the environmental science that so much of our activism and certainly our state laws are premised on also assume access to land for settler and colonial (and industry) goals, needs, and desires. That is, it's based on colonial land relations.

I'm saying that something good in one way can still also be colonial

The point is: Colonialism is not one kind of thing with one set of techniques that always align with capitalism or against environmentalism. I'm not saying environmentalism and science are inherently bad or inherently colonial. I'm saying that something good in one way can still also be colonial. This is why I argue that analyzing science and environmentalism from a colonial lens is important. It's a way of thinking that lets you zoom out to think about what seems normal and who or what that serves, and where change might better be directed.

Your book focuses on plastic pollution as the primary case study. With a growing plastisphere, what are the intricate ways in which plastic marks its presence within environmental, colonial and capitalist systems? How can one make themselves aware of this presence?

I think people are pretty aware of the presence of plastics in environments. Scientists and the media are constantly releasing new reports of plastics in new and less accessible places. Last week I think it was plastics crossing the placenta. A few weeks before it was plastic fibers in lungs. Before that, the Mariana trench, table salt, Mars, and Antarctica.

The trick is to see the ways plastics show the contours and limits of environmental, colonial and capitalist systems.

The trick is to see the ways plastics show the contours and limits of environmental, colonial and capitalist systems. For example, one of my favourite graphs shows the production of plastics worldwide from 1945 to the present. The graph is telling, not just because of its hockey-stick shaped graph of acceleration, but, first, because it starts at 1945 even though plastics have been produced since the 1880s. Those graphs don't start in the 1880s because there would be a flat line showing no growth for decades and decades. That makes a boring graph, but an interesting insight into the economic systems that define what plastics are today--cheap, disposable, and mass-produced. Which is recent and not how plastics have always been. Secondly, there are two moments in that graph where world production drops, even if only for a moment. The first is the energy crisis of the 1970s when oil and gas were scarce, and the second is the 2008 financial crisis. It shows the type of pressures that impact plastic production---not recycling (the graph doesn't even hesitate in 1970) or the rise of the circular economy, but in extraction, financialization, and industry's access to capital.

With its ubiquitous presence and incorporation into our ecological systems (for instance, in marine ecosystems), how can we learn to live with plastics rather than dream of a utopia of a world devoid of it?

Plastic pollution and disposability are what is called a stock and flow problem. So is an overflowing bathtub. If you walk into your bathroom and your tub is overflowing, do you get a mop, or do you turn off the facet and then get a mop? Hopefully the latter, or else you'll be mopping forever. So while the plastics that have already been created are going to be around for a while, we can also turn off the tap and find various ways to halt or mitigate the production of plastics, especially packaging and other key disposables. Then we can turn our attention to the plastics that are already here. That's not a utopia, but it is the ecological choice.

What is, according to you, a ‘good’ science? What sort of ethics would it bring to the table and who decides these ethics? Is there a collective responsibility that needs to be employed?

The way I understand it from my scientific training, good science is accountable science. That can be accountability to validity, replicability, and transparency of methods, as per the values in dominant science. And it can also mean accountability to land and to legacies of genocide, colonialism, sexism, and other systems that have benefited from science and continue to shape scientific inquiry and culture.

Plastic pollution and disposability are what is called a stock and flow problem. So is an overflowing bathtub. If you walk into your bathroom and your tub is overflowing, do you get a mop, or do you turn off the faucet and then get a mop?

Anticolonial science is one name for a specific set of accountabilities that have been articulated by many, many Indigenous thinkers, activists, philosophers, scholars, and lawyers. For example, accountability to fish as kin in some Indigenous legal frameworks means that you have to kill fish well and take care of their environments. That includes as a scientist. So, as a scientist that researches plastics in fish, I only use fish that have already been killed for food and I don't use chemicals in our research that are known to cause harm in aquatic environments. At the same time, I publish my methods so they are replicable and transparent, and validate my findings using statistics and peer review. You can be--must be--accountable to overlapping communities with different ideas of ethics and good science.

Ethics and responsibility are always collective. It would be weird to think they are individual decisions. Everyone is part of multiple collectives (families, communities, inhabitants in an ecosystem and neighbourhood, professions, workplaces) whether we want to be or not. Ethics is another way to talk about accountability to those collectives, and those are always on the terms of the collective. Anticolonial science and ethics is a way to point out that one of those collectives is as beneficiaries or subjects of imperialism and colonialism.

You make aware that despite the best intentions towards a land, colonial relations can still be reproduced. How may redefining the relationship with our environments help us break out of this cycle of reproduction?

One of the primary ways that I think that colonialism and colonial relations to land is unintentionally reproduced is when people or groups conflate colonialism with all sorts of bad stuff: exclusion, racism, sexism, environmental harm, capitalism, exploitation, and wearing your shoes in the house. But all of those "bads" can be dealt with and the resulting goods can still assume settler and colonial access to land. See my point above about hydro dams and the commons. That means that inclusion, anti-racism, and recycling is assumed to address colonialism, except the same land relations that grant settler and colonial access to land are still firmly in place. Step one is knowing what colonialism is. There's a great article by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang called "Decolonization is not a metaphor" that goes through this. It's a great way to start redefining relationships to break out of cycles, as you say.

How can we become ‘better ancestors’ to futures to come?

Are you trying to talk Indigenous to me?

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

Be the first to comment